The Rise Of The Night-Fighters – Devastating Aircraft in Two World Wars

| SHARE:FacebookTwitter |

Fighting between planes began in daylight which allowed pilots and gunners to see what was going on so they could target their prey and see enemies attacking. There were advantages to flying at night though, so work began on the techniques and technology of night fighting.

Night Fighting in WWI

The first serious night fighting took place over Britain during WWI.

German airships, sent to bomb British cities, made use of the darkness to provide cover. They were flying over enemy territory far from home and needed every advantage they could get.

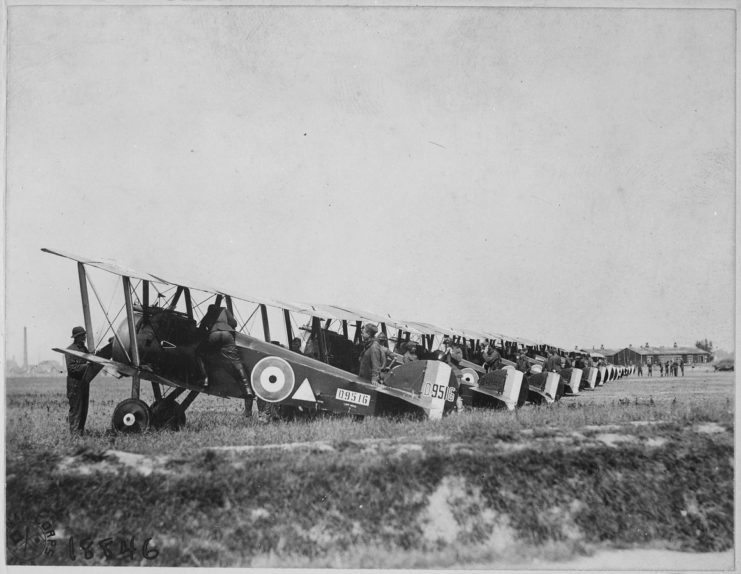

The British responded as well as they could with the resources they had. Bristol Fighters and Sopwith Camels soared into the sky, just as they did during the day, to take on the aggressors. They had no specialist equipment to help them see in the darkness. They had to rely on their eyesight, hoping for a bright moon to illuminate the bombers. Their successes were small.

The Start of WWII

During WWII night fighting was much more significant. Huge waves of bombers used darkness to protect their lumbering and vulnerable frames from enemy fighters and anti-aircraft guns, as they pounded their enemy’s military and industrial facilities. First in the Battle of Britain, then in Allied strikes against Germany, and then in attacks on mainland Japan. Night-time bombers struck the heartland of all the combatants.

Technologically, things had changed a little. Bright searchlights scoured the skies above cities, trying to illuminate bombers as they came in on their attack runs. It was a hit or miss business.

Radar was a more important step forward. Ground-based radar stations identified incoming enemy aircraft and directed fighters to them.

Once the planes were in the sky, everything was much as it had been during WWI. Pilots rushed around in the darkness, flying the same planes they used in daylight, trying to shoot enemies illuminated by the moon and stars.

Enter Airborne Radar

America, Britain, and Germany were all working on technology that would change the game entirely. It was airborne radar.

If a plane could be equipped with its own airborne radar, then it could target enemy aircraft without having to see them. The gun sights of planes had already moved away from basic physical ones. It was the logical next step.

The British, working in secret, were the first to achieve success with airborne radar.

They had already moved Bristol Blenheim fighters, outclassed in daylight by the German Bf109, into a night fighting role. They equipped some of those planes with radar.

In July 1940, a Blenheim destroyed a Dornier Do 17 in a night fight. It was the first successful intercept using airborne radar.

Night fighting was coming into its own.

The Bristol Beaufighter

Retro-fitting radar onto existing planes was a useful step, but what was really required was a purpose-built night fighter. Designed for the unique circumstances of fighting in the dark, with its radar equipment built in, it would give its pilots a huge edge.

The British, building on their success with the Blenheim, were the first to field a high-performance purpose-built night fighter. It was another Bristol model; this time named the Beaufighter.

The Beaufighter was fast and maneuverable if a little difficult to handle on takeoff. With four 20mm cannons and six 7.7mm machine-guns, it had the heaviest armament of any fighter in the air. Its radar had a range of four miles, allowing pilots to close in on their enemies for the kill.

American Efforts

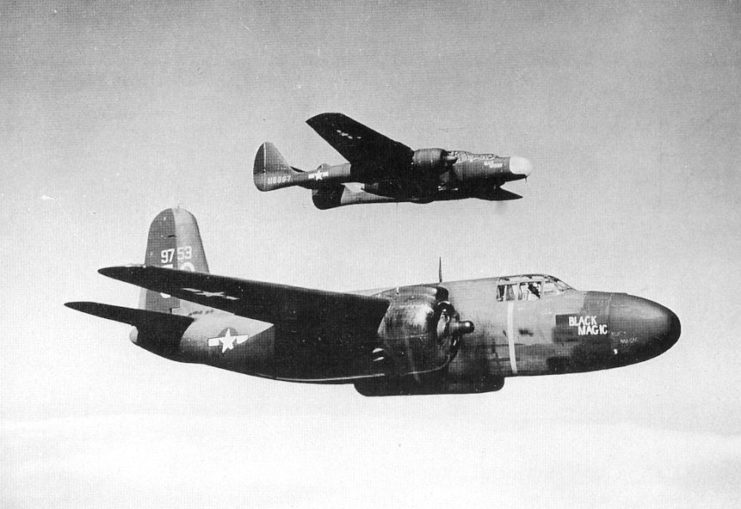

Beaufighters were purpose built for night fighting, but it was not the role the aircraft had originally been designed for. Instead, they were a purpose-built variant on an existing model. The first purpose-designed night fighter was American.

The Northrop P/F-61 Black Widow was designed in response to the RAF’s night fighter success in 1940. It entered production late in 1943 and first saw action in July 1944. In its first European engagement, the Black Widow destroyed four German planes. Around the same time, it had its first successes against Japanese planes in the Pacific.

Interim measures were needed while the Black Widow was designed and produced. For the first few years of the war, American forces used the Douglas P-70 as an adapted night fighter. In Europe, they also used British Beaufighters.

German Nightfighters

Although ahead of the Allies in many areas of military technology, the Germans were behind in the race to field airborne radar. They spent the first few years relying on day fighters, ground radar, and searchlights. It was not until the summer of 1942 that they started fielding fighters that carried their own radar.

Two German planes became particularly noteworthy night fighters.

The Messerschmitt Bf110 had served well during the early days of the war, escorting bombers on their missions. Enemy fighters outclassed it and, like the Bristol Blenheim, it was relegated to night-time defense duties. When the first German airborne radar became available, it was fitted to the latest model, the Bf110F-4. With its four machine-guns and two cannons, it became a hard hitting night-time interceptor.

Also noteworthy was the Junkers Ju 88. A versatile three-seater aircraft, it carried several guns that fired diagonally upward, allowing it to attack high-flying bombers from below. It was one of Germany’s most effective defensive measures.

Countering the Nightfighters

The success of the night fighters led to counter-measures. Among them was “Window,” an RAF technique in which bundles of aluminum strips were dropped from bombers. They confused the radar, making it hard for the Germans to attack them.

Such simple measures could not change the fact that night fighting was here to stay. Purpose-built planes with purpose-built equipment could fight each other effectively at night. The war in the skies would never be the same.