The McDonnell XF-85 Goblin was a fighter aircraft, conceived during World War II and intended to be carried in the bomb bay of the giant Convair B-36 Peacemaker bomber as a defensive “parasite fighter”. Because of its small and rotund appearance, it was nicknamed “The Flying Egg”.

The XF-85’s intended role was to defend bombers from hostile interceptors, a need demonstrated during World War II. Two prototypes were constructed before the program was terminated.

The XF-85 was a response to a United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) requirement for a fighter to be carried within the Northrop XB-35 and B-36, then under development. This was to address the limited range of existing interceptor aircraft compared to the greater range of new bomber designs. The XF-85 was a diminutive jet aircraft featuring a distinctive egg-shaped fuselage and a forked-tail stabilizer design.

During wind tunnel testing at Moffett Field, California, the first prototype XF-85 was accidentally dropped from a crane at a height of 40 ft, causing substantial damage to the forward fuselage, air intake and lower fuselage. The second prototype had to be substituted for the remainder of the wind tunnel tests and the initial flight tests.

As a production series B-36 was unavailable, all XF-85 flight tests were carried out using a converted EB-29B Superfortress mother ship that had a modified, “cutaway” bomb bay complete with trapeze, front airflow deflector and an array of camera equipment and instrumentation. Since the EB-29B, named Monstro, was smaller than the B-36, the XF-85 would be flight tested, half-exposed. In order to carry the XF-85, a special “loading pit” was dug into the tarmac at South Base, Muroc Field, where all the flight tests originated. On 23 July 1948, the XF-85 flew the first of five captive flights, designed to test whether the EB-29B and its parasite fighter could fly “mated”. The XF-85 was carried in a stowed position, but was sometimes tethered and extended into the airstream with the engine off, for the pilot to gain some feel for the aircraft in flight.

McDonnell test pilot Edwin Schoch was assigned to the project, riding in the XF-85 while it was stowed aboard the EB-29B, before attempting a “free” flight on 23 August 1948. After Schoch was released from the bomber at a height of 20,000 ft, he completed a 10-minute proving flight at speeds between 180 and 250 mph (290–400 km/h), testing controls and maneuverability. When he attempted a hook-up, it became obvious the Goblin was extremely sensitive to the bomber’s turbulence, as well as being affected by the air cushion created by the two aircraft operating in close proximity. Constant but gentle adjustments of throttle and trim were necessary to overcome the cushioning effect.

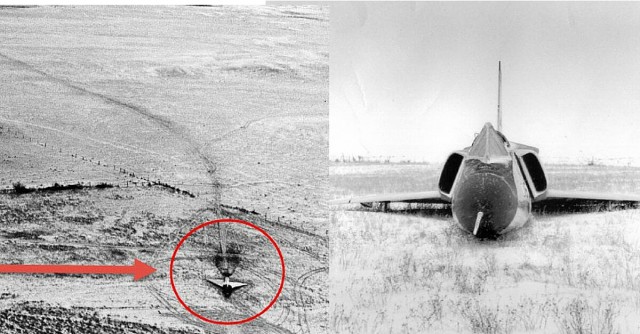

After three attempts to hook onto the trapeze, Schoch miscalculated his approach and struck the trapeze so violently that the canopy was smashed and ripped free and his helmet and mask were torn off. He saved the prototype by making a belly landing on the reinforced skid at the dry lake bed at Muroc. All flight testing was suspended for seven weeks while the XF-85 was repaired and modified. Schoch used the down period to undertake a series of problem-free dummy dockings with a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star fighter.

- After boosting the trim power by 50 percent, adjusting the aerodynamics, and other modifications, two further mated test flights were carried out before Schoch was able to make a successful release and hookup on 14 October 1948. During the fifth free flight on 22 October 1948, Schoch again found it difficult to hook the Goblin to the bomber’s trapeze, aborting four attempts before hitting the trapeze bar and breaking the hook on the XF-85’s nose. Again, a forced landing was successfully carried out at Muroc.

Continued